The power of partnerships. Report of an end-of-programme workshop and a WASH Debate.

Published on: 18/10/2022

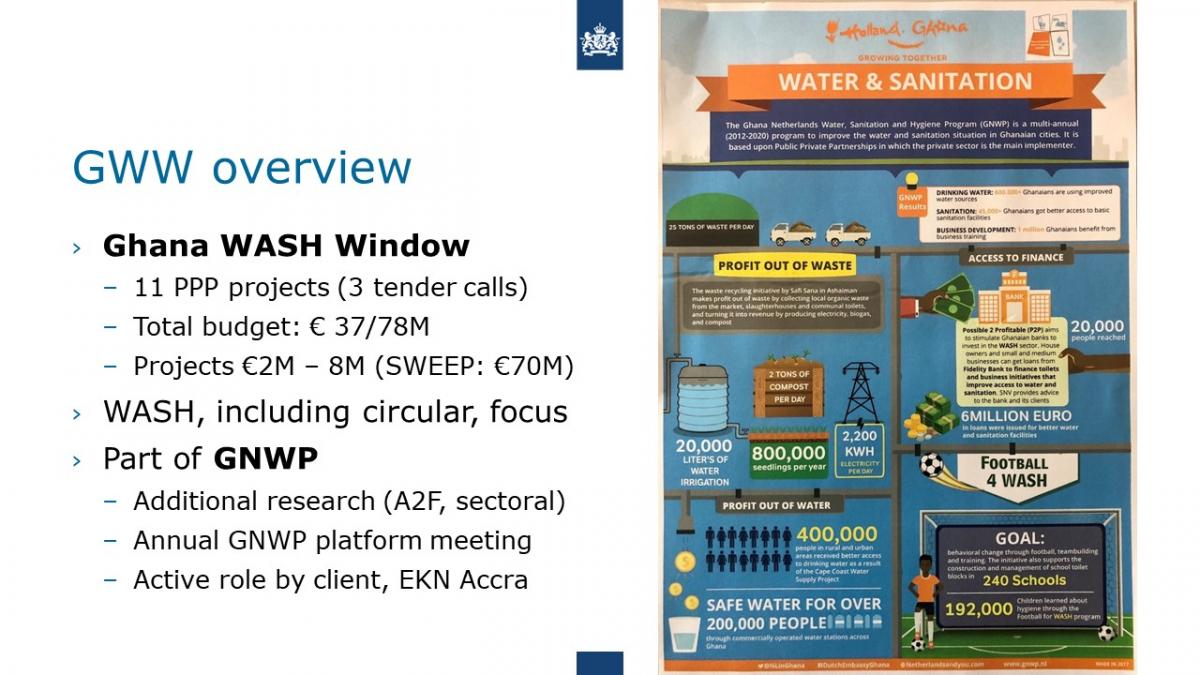

From 2012-2022, the Governments of Ghana and the Netherlands supported 16 integrated urban water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) projects as part of the Ghana-Netherlands WASH Programme (GNWP). The Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (EKN Accra) administered these projects: five independent projects were awarded grants while the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO) implemented the remaining 11 Public-Private Partnership (PPP) programmes. The PPP projects covered urban water, sanitation, solid waste management, faecal sludge and organic waste treatment, compost production, waste to energy schemes, hygiene education and WASH in schools.

Participants at the Ghana Netherlands WASH Programme Workshop on Sustainable Services and Exit Strategies 29 June 2022. Photo credit: IRC Ghana

IRC and RVO co-hosted two events to mark the end of the GNWP, one in Ghana and one in the Netherlands. The GNWP Annual Meeting held on 29 June 2022 in Accra focused on Sustainable Services and Exit Strategies. The event in The Hague hosted a WASH Debate on public-private partnerships. This event, that took place on 26 September 2022, was open to the general public and discussed the strengths and limitations of PPPs in WASH. In this article, we present the highlights of the proceedings of both events.

At the workshop held in Ghana, the Netherlands Embassy's WASH and Climate Policy Officer, Ms Janet Dufie Arthur, explained that the emphasis of the GNWP has been on sustainability of interventions, through sustainable financing models with more private sector engagement to build capacity and behaviour change communication. The first phase of the programme included the development of five municipal master plans, including infrastructural development, capacity building for municipal assemblies and review of by-laws.

In the GNWP programme's second phase various PPP business cases have been developed, shared Dr. Gábor Szántó, the coordinator of the Ghana WASH Window (GWW) programme. He added that the PPPs stimulated mutual capacity strengthening and succeeded in generating revenues covering operation and maintenance costs. In some cases, the initiatives triggered or contributed to WASH system changes. These systems changes were attributed to the introduction of replicable innovations at project level and in service delivery improvement, which were recognised by local policymakers.

Some examples of measures that ensured sustainable services included investigating the credit worthiness of sanitation loan applicants and subsidised interest rates, implementing water safety plans, using prepaid smart meters and mobile money technology and promoting the use of cheaper reusable sanitary pads.

The Ghana workshop participants were asked to reflect on how the ending of the GNWP impacted the sustainability of their projects. Out of the 18 responses, 61% felt that their progress ensured that the GNWP would affect their initiative and believed that their efforts led to the full or at least partial achievement of their project goals. 44% indicated that they have already scaled up their projects while 16% indicated they had developed plans for a scale up. 66% of the respondents indicated that access to additional funds was challenging but doable.

Participants identified threats to sustainability including a restricted financing infrastructure for scaling up, limited enforcement of the legal framework and the difficulty to ensure lasting government commitment. The new Public Private Partnership Act, 2020 (Act 1039), which was passed in Ghana on 29 December 2020, meant PPPs took longer to implement but provided more clarity on roles and responsibilities among partners.

Participants confirmed that the annually held GNWP meetings provided a beneficial platform for knowledge sharing, networking and forging relationships between the private sector, NGOs, Ghanaian authorities and the Netherlands Embassy.

The end of the GNWP coincided with the end of the Dutch government’s development relationship with Ghana in 2020 and was in line with the 2019 Ghana Beyond Aid charter and strategy.

H. E Ambassador Verheul explained that the Embassy will “respectfully” phase out of WASH in Ghana. The Embassy is shifting its focus from aid to trade, specifically geared to the agricultural sector. The Ambassador noted, however, that other Netherlands government institutions will continue to work with the WASH sector. Examples include the Blue Deal programme, aimed at exchanging water management knowledge with other countries and WaterWorX, which is a partnership of public water operators to increase access to sustainable water services for 10 million people between 2017-2030. A new institution, Invest International, has been endowed with investment capital by the Dutch State to invest in major projects and will take over some of the instruments managed by RVO. The Ambassador mentioned that the Embassy will conduct an evaluation of 10 years of Dutch investment in the Ghana WASH sector.

Mr. Michel de Zwart, the former coordinator of the Ghana WASH Window (GWW), opened the WASH Debate by highlighting the largely achieved economic output targets and the PPPs strong approach and sound innovative business models. Nevertheless, he remarked that access to finance remains an obstacle because of the limited interest and availability of financing institutions for the WASH sector and the often unrealistically high interest rates of financing products.

Credit: Michel de Zwart

The event showcased four GNWP/GWW presentations to fuel the debate. The first of the four WASH Debate presentations came from Ms Janet Dufie Arthur and described the original vision of the Netherlands Embassy in Accra to set up the GNWP/GWW programme. Besides improving access to WASH services, she noted that the PPP projects were meant to enhance capacities of municipal assemblies, increase private sector involvement for lasting improved WASH access and deliver opportunities for the eventual scaling up of sustainable urban WASH services.

She explained that PPPs helped influence policy partly thanks to the GNWP annual meetings and other multistakeholder project forums where government representatives sat at the table. A prime example is when UNICEF, that works closely with the national government, also adopted market-based approaches to sanitation, which is now included in Ghana’s national sanitation policy.

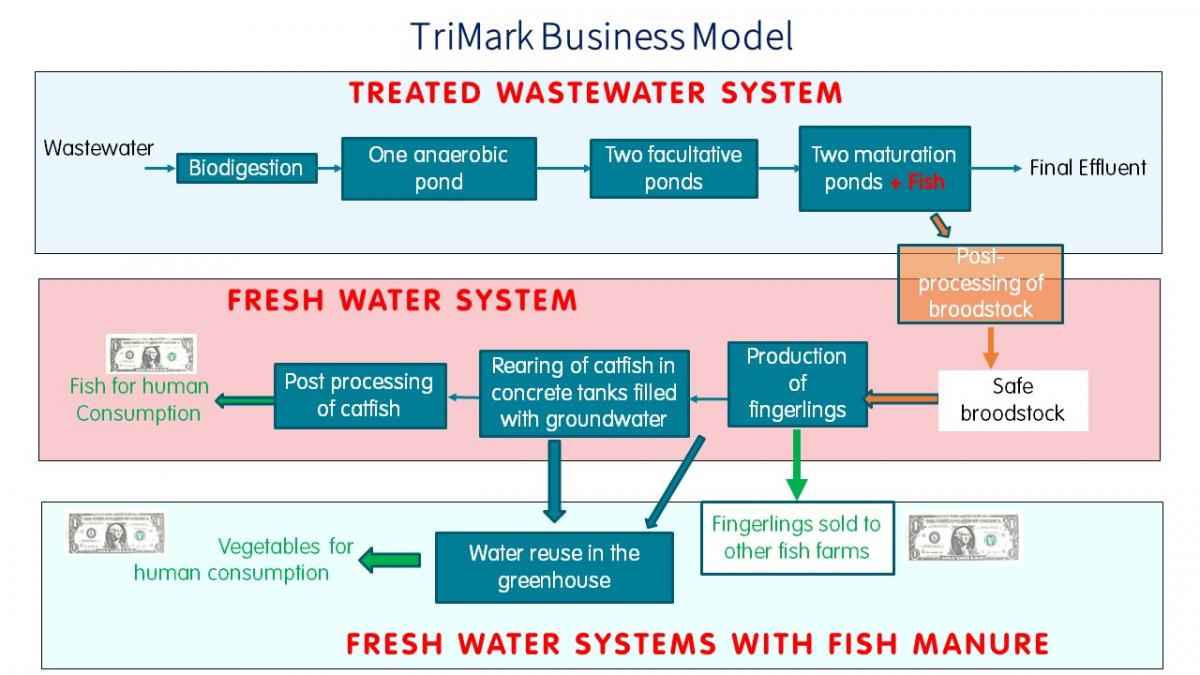

IWMI consultant Dr. Philip Amoah presented circular waste management innovations that were developed in the CapVal project. The innovations included turning faecal sludge and organic solid wastes into safe compost, turning various local wood wastes into non-carbonised briquettes for fuel, and using treated wastewater for fish production. Part of the revenue generated, said Dr. Amoah, can be used to pay the operation and maintenance costs for system treatment plants.

Credit: Dr. Philip Amoah

There are big business opportunities for the production of organic compost since cheap imported chemical fertiliser is no longer available because of the war in Ukraine, according to Ms Janet Dufie Arthur. Dr. Amoah stated that the wastewater-fed aquaculture model had strong potential for replication in developing countries where there are functioning wastewater treatment plants.

Most of the developed innovations are considered 'first-of-its-kind' in Ghana. The quality of the results prompted the awarding of various prizes and led to additional financing of the managed facilities.

Mr. Joseph Ampadu-Boakye serves as Safe Water Network's Head of Partnerships and Business Development in Ghana. He presented lessons from their water access initiative project, which used a market-based approach for rural water supply, as well for schools and health care facilities based on the Safe Water Enterprise (SWE) model. The challenge was to leverage funding to increase the number of piped connections to Bottom of the Pyramid (BoP) communities. Key success factors included demand creation through door-to-door extension work and engaging with government, private sector and academia in a PPP/SWE working group forum. In September 2022, the Safe Water Network received US$ 20 million to scale up its water access development efforts in Ghana

The final presentation was by Ms Emma Lesterhuis, VEI Regional Manager South-West Africa and project manager for the Football for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene project. The project used the FIETS framework to assess its sustainability. Ms Lesterhuis explained how technical sustainability was achieved after schools were convinced to switch from pour-flush latrines (with high water costs) to cheaper dry toilets built with local materials. Football supports social sustainability by connecting people and creating safe spaces to learn about hygiene, COVID and inclusiveness. Merck, the project’s private sector partner brought in technical expertise on water quality to help ensure environmental sustainability.

In the subsequent panel discussion, Mr. Fred Smiet reminded the audience that 10 years ago there was very little experience with PPPs in Ghana. As former First Secretary and WASH officer at the Netherlands Embassy in Ghana, he was involved from the start in the selection of projects for the Ghana WASH Window (GWW) programme and was proud of the achievements in pioneering PPPs.

Mr. Michiel Slotema, from RVO’s Sustainable Water Fund, concluded that essentially “we are all doing the same thing but then geared to attaining sustainability” so that PPPs become more effective, reach scale and can be replicated. He added that some private partners don’t need incentives if they see a clear business case in a PPP. While subsidies can help de-risk investment in PPPs, free water initiatives can act as a deterrent. When VEI encountered high water bills in schools, they were able to recover some of the costs by asking vendors for a small contribution.

Dr. Gábor Szántó added that the GWW had set out to pioneer and prove concepts for difficult WASH contexts and not to harvest the “low hanging fruit". All 11 eleven projects were proof of concepts that hadn’t been tested yet in Ghana. Most PPPs were proved at least partially successful, and the failures were primarily due to external factors.

To aid the debate on PPP quality in WASH interventions, IRC’s Ingeborg Krukkert talked about a typology of PPPs that IRC had developed for a study commissioned by RVO’s Sustainable Water Fund. The study distinguished three levels of intervention: reshaping the rules (policy influencing), re-enforcing public institutions and responding to a public need (a market-based response). In practice PPPs may go through difference phases, e.g., starting with market-based approaches and then engaging in policy influencing.

When asked how PPPs could be made adaptive, Ms Janet Dufie Arthur said what helped was a partner from government especially when permits are required or to influence policy,

IRC’s Stef Smits closed by presenting his takeaways from the debate:

All projects have partnerships nowadays so what specifically makes PPP projects, such as the those presented at the event, different? There is no simple answer to that. The cases show that public, private and NGO/knowledge partners play essential but complimentary roles in these PPPs. For example, the public sector may play the role of co-investor as shown in the case of Safe Water Network (co-investor). The public sector may have a role in creating an enabling environment, in being the owner of infrastructure and regulating the issuance of permits. The private sector can either: 1) contribute as part of its corporate social responsibility (CSR) mandate, 2) act as an operator or 3) have a role in the supply-chain, for example selling by-products of waste. Key is what brings it all together. There appear to be two ways. First is the setting up of the businesses, the enterprises and focussing on sustainability - both financially in terms of a sustainable business model, and in the environmental, technical and social sense. The second pathway is scaling up, going from responding to immediate needs to sorting out your roles more quickly and enhancing the role of the public sector and eventually leading to broader systems change.

Watch the recording of the WASH Debate below.

To learn how far you can go in PPPs, read the RVO article "Making partnerships work: The FDW programme approach" based on the Sustainable Water Fund policy brief and review listed under Resources.

Visit the Ghana-Netherlands WASH Programme (GNWP) website and watch the video about the Ghana WASH Window below